With members across the UK, the BBSA is the single largest source of independent information on the solar shading industry. The BBSA sponsors two PhD Researchers and has a wealth of technical and scientific know-how.

Solar shading should be part of building services

Solar shading should be part of building services

The term “Overheating” is not clearly defined.

CIBSE TM52: The limits of thermal comfort: avoiding overheating in European buildings, suggests following BS EN 15251 to determine whether an existing occupied building can be classed as overheating or a proposed building is in danger of becoming overheated.

BS EN 15251:2007 provides recommended operative temperatures for different room purposes. Depending on the season, bedrooms and living areas are recommended to remain between the temperatures highlighted opposite.

These temperatures represent the upper and lower limits of thermal comfort. The World Health Organisation (1990) recommended that although the range 18ºC - 24ºC are suitable for healthy sedentary people, for vulnerable groups air temperatures should be maintained at 20ºC.

For homes further help is on hand with TM59: Design methodology for the assessment of overheating risk in homes, TM60: Good practice in the design of homes.

The table below is taken from CIBSE’s Environmental Design Guide A, 2015 and shows the peak operative temperatures for the design of buildings.

The Zero Carbon Hub's report, Overheating - The Big Picture, (2015) highlights the key causes of overheating identified by the NHBC (Understanding Overheating - Where to start, 2012):

External pollution and excessive noise may prevent occupants from opening their windows. Surrounding hard surfaces will absorb heat and release this during the night.

On a warm, still day when external temperatures are high, fresh air may not provide enough of a cooling effect to address overheating.

Double-glazed windows with a low-e coating prevent heat from escaping. Houses with unshaded west-facing glass will suffer from higher levels of solar gain in the warmer part of the day.

Electrical appliances, occupant activities such as cooking, and building services, e.g. boiler and hot water storage, all have the potential to radiate heat that may contribute significantly to the increasing internal temperatures.

Modern homes have increased levels of insulation and airtightness, resulting in more heat being retained within the homes. This means any built-up heat in the homes will have to be actively removed.

User behaviour - “There is evidence that people lack a basic understanding of the risks of health from high indoor temperatures, and are therefore less likely to take measures to safeguard their and their dependents’ wellbeing” (Committee on Climate Change - UK Climate Change Risk Assessment, 2017).

Increased urbanisation – In the UK we are increasingly becoming an urbanised nation. By 2050 it is expected that 90% of the UK’s population will live in urban areas. Currently we spend 90% of our time indoors and 65% in our homes. As our cities expand typically buildings become high rise. More urbanisation creates the urban heat island effect will make external temperatures hotter.

Culture – The UK has been a heating nation, not a cooling one. We are not used to high temperatures, unlike say our southern European neighbours who have a long tradition of using external shading on their buildings. There is a body of evidence which shows that in the UK we do not know how to operate movable solar shading to maximise its benefit.

Solar shading should be part of building services

Solar shading should be part of building services

The Zero Carbon Hub’s report Overheating – The Big Picture (2015) highlights the key economic and social effects of overheating:

The sun is an ever-changing force throughout the day. Dynamic solar shading can significantly help improve the internal environment of buildings by:

Controlling solar gains

Research conducted on apartments in north London showed that external shading could reduce internal operative temperatures by 10 – 18ºC and internal shading by 8 – 13ºC (at 95% confidence levels) – see more here.

The importance of Gtot

The critical measure is Gtot which is a measure of the total energy transmittance of the glazing in combination with the blind or other shading when exposed to solar radiation.

Reducing energy demands

The National Energy Foundation (NEF) have conducted building modelling in EnergyPlus which shows HVAC savings of up to 54% with external shading and up to 16% with internal shading.

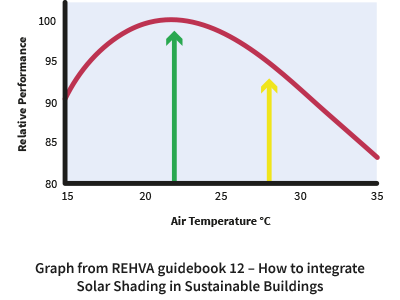

In REHVA guidebook number 12 it was shown across three cities in Europe that the payback on solar shading was less than a year.

Providing remote control and feedback

Dynamic solar shading allows for remote monitoring and feedback of the position of solar shading and can integrate with building management systems for the ultimate control of thermal and optical comfort.

In addition solar shading can help retain wanted heat during the cooler months by acting as a thermal barrier to the glazing, can control daylight and glare and is typically a low cost, passive solution.

The resources detailed below are specific to the overheating CPD produced by CIBSE in conjunction with the British Blind and Shutter Association. There are other useful resources available here.